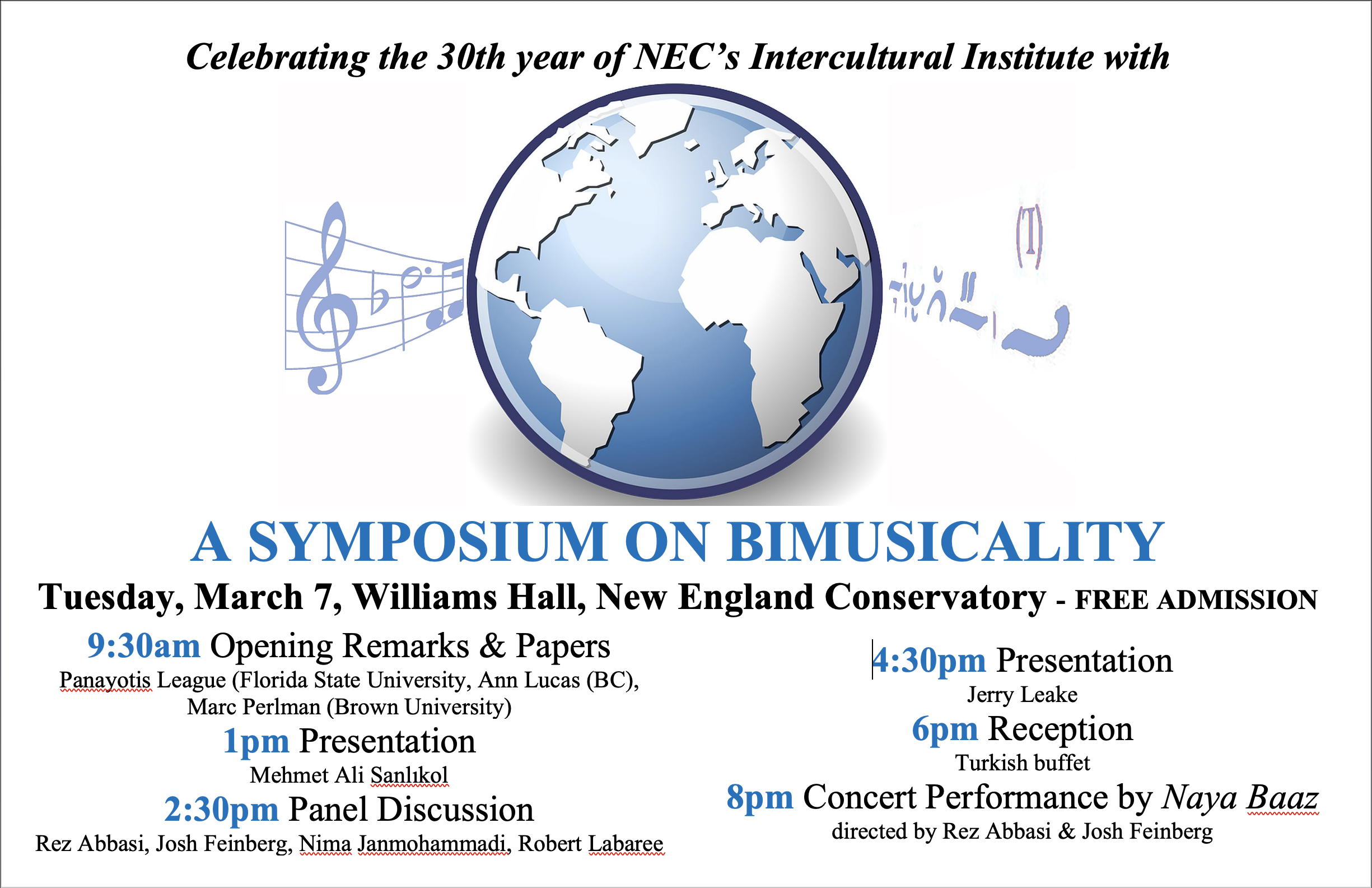

Bimusicality Symposium

The age of YouTube did not diminish our obsession with the 'other' and cultural appropriation issues in any way. If anything, these issues are far more relevant now. So, how are 21st century musicians supposed to become culturally equipped to develop awareness toward these issues? This symposium will approach this matter from the perspective of Bimusicality, a concept which refers to musicians who are able to perform and express themselves in two musical traditions. While this concept was first suggested by ethnomusicologist Mantle Hood in 1960, the world has changed significantly since then with musics from around the world becoming far more accessible but not necessarily any more quickly attainable as mastering a musical tradition still takes many years. It is our aim at this symposium to present the many possible bi- and multi-musicalities that 21st century musicians experience and explain how both appropriation and internalization can be part of their music making.

The symposium is directed by NEC faculty, award winning composer/performer and scholar Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol.

9:30am Opening Remarks & Papers (Scroll down for abstracts)

Panayotis League (Florida State University, Ann Lucas (BC), Marc Perlman (Brown University)

1pm Presentation by Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol

2:30pm Panel Discussion

with Guggenheim winner Pakistani-American jazz guitarist Rez Abbasi, NEC alum and sitarist Josh Feinberg, NEC faculty and noted composer/performer Nima Janmohammadi, and former NEC faculty Robert Labaree (moderator)

4:30pm Presentation by NEC faculty Jerry Leake

6pm Reception

Turkish buffet

8pm Concert Performance by Naya Baaz

directed by Rez Abbasi & Josh Feinberg

Multi-Musicality and the Persistent Problem of Representation (Panayotis League, Florida State University)

As a multitude of scholars and artists have consistently pointed out, Hood's bi-musicality as method-practice-lifeway remains a relevant and generative concept even as it is becoming increasingly common for musicologists to study traditions to which they "belong" in various ways separate from scholarly projects. As the field continues to expand and conversations are being driven by voices and perspectives that were notably absent in previous generations, we keep coming back to one of the fundamental issues posed by the practice of ethnography, albeit from different angles each time: how do we responsibly and productively navigate the tensions and power differentials inherent in scholarship that is necessarily subjective and even autobiographical, on the one hand, and fundamentally concerned on the other with the fictive representation of human beings and their social-artistic-emotional lives in a context explicitly framed as non-fiction? This presentation explores some of the epistemological and practical problems raised by this issue from my perspective of a US-born scholar/practitioner who was raised between several different musical cultures (those of Greek Aegean island and Irish migrants as well as American popular music) and who, despite almost two decades of immersion in another tradition (that of Northeastern Brazil), continues to struggle to find ethical ways to engage as a researcher and artist with the latter. I detail some of these struggles, discuss a few of my attempts to make friends with them, and suggest some of the ways that they have begun to inform my relationship with the musics and lifeways that I have been participating in since my youth.

But Whose Music Is It?

Some Reflections on Bimusicality in Research vs. Education (Ann E. Lucas, Boston College)

The concept of bimusicality was introduced by Mantle Hood as a critique of how “Occidental” ethnomusicologists analyzed “Oriental” music (1960). Hood criticized researchers who did not develop their own musicality and musicianship in the music they were researching. The basic concept of “bi-musicality” was that researchers should learn to play their music of study how indigenous musicians learned it and engage in performance in the same way indigenous musicians performed it. In Hood’s view, such hands-on practicum was necessary for researchers to be able to correctly analyze a music tradition in cultural context. More recently, however, Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol has argued that bimusicality is a much more relevant concept for all applied music studies in the 21st century (2020). Rather than seeing it as a starting point for research, he sees bimusicality as a missing part of any music practitioner’s education, in a world where nearly all music on earth is accessible to nearly everyone. This paper reflects on how both of these ideas of bimusicality have played out in my own research in the Middle East as well as my work running a university Middle East Ensemble. Hood’s ideas about how it applies in research present some challenges in context when considering musical change in historical research as well as the complicated nature of culture writ-large vis-à-vis specific ethnographic contexts. Conversely Sanlıkol’s approach seems very relevant in the context of music education in American institutions of higher education, even as it also presents challenges that need to be addressed.

Bimusicality and the Politics of “Universality” (Marc Perlman, Brown University)

Bimusicality seems simple enough to define by analogy with bilingualism, but it harbors many ambiguities. All human languages are learned equally well by all children, but not all children acquire advanced musical abilities. Do musical traditions differ in their degree of susceptibility to appropriation? It has been suggested that some traditions—especially European art music—are more “universal” than others, more accessible to learners from any and all societies or cultures. It is true that European art music has practitioners all over the globe, but what is the significance of that fact? In this presentation I consider this question and draw out its implications for musical traditions that are not usually considered “universal.”

ALL EVENTS ARE FREE AND OPEN TO PUBLIC

Founded in 1993, the Intercultural Institute is a budgeted department of the New England Conservatory charged with providing monthly programming in a wide range of non-western musics of the world for the conservatory community and the public. Distinguished guests over the years have included Blue Heron, Umalali, Huun Huur Tu, Boston Village Gamelan, Christos Zotos, Erkan Oğur, Cinuçen Tanrıkuror and Hafız Kani Karaca.