Disrupting the Traditional Conservatory Model at the Intersection of Climate Change, Culture, and Performance

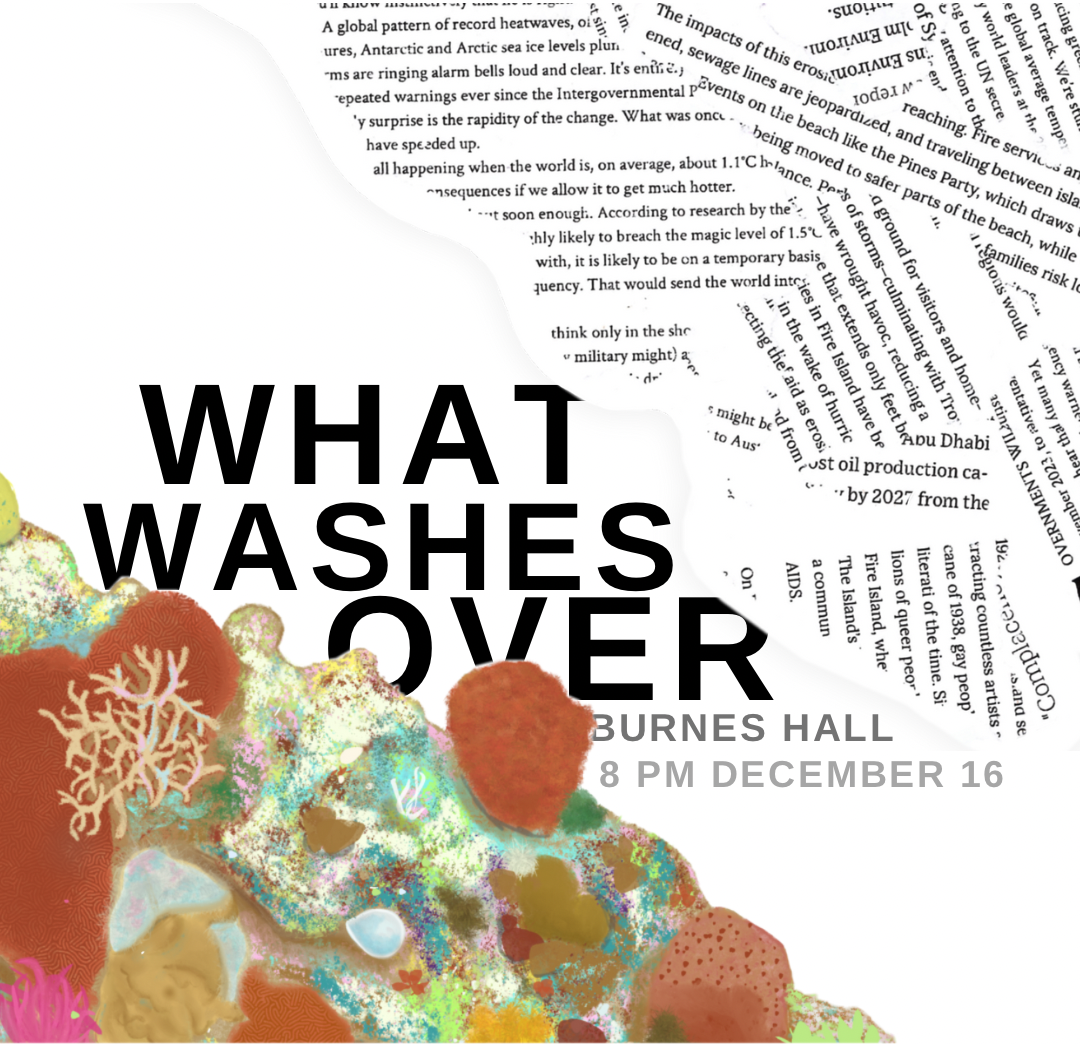

The day after fall semester classes ended, as students, faculty, and staff began retreating from campus to enjoy the start of winter break, a crowd formed in Burnes Hall at New England Conservatory. A layered mixture of human, natural, and machine noises draped the space in a continuous soundscape as audience members drifted in and a group of conservatory students prepared to perform. The crowd had gathered for What Washes Over: Sounds of Climate Grief and Action, the culmination of Climate Change Culture and Performance Practicum, a new course offered at NEC last fall as part of its integrative curriculum.

NEC’s integrative courses disrupt the traditional conservatory education model by connecting theory and practice across disciplines. Courses like Climate Change Culture and Performance Practicum, Creativity and Manuscripts, Performance and Analysis: Beethoven's Violin Sonatas, and Music of Turkey and the Ottoman Period are akin to practice rooms for the world beyond NEC. Learning goes beyond the classroom, encouraging investigation and inventing, sparking curiosity and, in turn, creating better thinkers and performers.

Climate Change Culture & Performance Practicum

Taught by Liberal Arts professor Dr. Jill Gatlin, Climate Change Culture & Performance Practicum is a new addition to NEC's growing integrative course offerings. Gatlin, who began teaching at NEC in 2008, has a Ph.D. in English with an emphasis on environmental studies and a bachelor’s degree in music. She researches the intersection of literature, visual culture, and environmentalism—a blend ideally suited to the learning goals of this course, which combines a classroom component (Climate Change Culture) with a project-based workshop component (the Performance Practicum).

During the Climate Change Culture portion of the course, Gatlin and students explored how the emotions, psychological processes, and cultural values of populations shape perceptions of climate change beyond scientific analysis ("At least 97% of climate scientists agree that climate change is a real threat with human causes, yet only half of Americans are aware of this consensus. Meanwhile, popular debates on climate change—and what to do about it—persist," the syllabus reads). Students examined scholarly studies, artwork, literature, cultural communication, and political activism to comprehend how human beings understand and respond to climate change and what ethical problems and local and global inequities arise as a result of a warming planet.

One study students examined came from Lauren Oakes, whose research documented that certain tree species in Alaska's coastal forests will die out due to warming temperatures, triggering an enormous shift in the species living on the forest floor. Oakes's study was not widely read and received little traction when first published. However, when her colleague, Nik Sawe, utilized a process known as data sonification to translate the raw numbers of the Alaskan tree study into music, the result was a classical composition that offered listeners a sonic representation of tree death over time. The impact of this startling piece of music on the scientific community and beyond was much more significant than that of Oakes's original study — demonstrating the unique power of art on human perceptions of consequential topics like climate change.

This Alaskan tree study was part of a common thread through Gatlin's course that propelled students forward as they worked through the Performance Practicum portion. They were challenged to design, produce, and execute a concert program that embodied their new understanding of how art, literature, and music can be effective tools for social change.

What Washes Over: Sounds of Climate Grief and Action

Over several class sessions, the students in Gatlin’s course collaborated to develop the concept for What Washes Over, each taking responsibility for different thematic and technical components. With careful consideration of how to most effectively and appropriately tackle a topic as immense as climate change at one concert without muddling their message, they developed the following program summary, emphasizing hope as it relates to action: “What Washes Over is a multimedia exploration of how we relate to a changing climate, how we make space for grief, care, action, and resilience, and how we create community and connect with life across the planet.”

“While there were many subtleties to the academic and performance outcomes for the course, the main integrative outcome was for students to apply their thematic learning and academic skills to design and produce a performance related to climate change culture, gaining professional skills in the process,” explained Gatlin. “I wanted the course to inspire exploration and expansion of the ways students imagine and present themselves as multi-skilled, multidisciplinary artists and to give them confidence in designing and carrying out collaborative, public-facing projects. I did not anticipate the range of roles they’d all fill or some of the more nuanced skills they’d gain—one of those skills was certainly the deep collaborative care and trust they developed.”

One student, Seth Goldman ’25, a classical bassoonist, acquired software programming skills to create the soundscape that filled the space, utilizing more than 50 recordings provided by class members. Another, trumpeter Matthew Mihalko ’24, cultivated management skills as he commissioned works from composers outside of the class, effectively communicating his vision for the music while making space for the composers’ vision. Vocalist Helen Bultman ’25 developed an understanding of music licensing laws in order to perform copyrighted works, and another, bassoonist and composer Evan Judson ’24, refined his compositional notation skills in ways they had not considered or attempted before.

“I’m learning over and over that the work that we all did here was not just on climate change, but also on presentation, on accessibility and approach, cultural normativity and disruption, communication, and community,” said violist Phillip Rawlinson ’25. Inspired by the concept of data sonification, Rawlinson created “mechanizations of flow,” a sonic piece made up of machine sounds representing the impact of rising sea levels on the people of the Carteret Islands in Papua New Guinea.

Another piece, “City Sinking, Harbor Rising,” written by composer Matthew Lanning ’23 MM, ’26 DMA, was a jazz-style piano concerto influenced by the music of George Gershwin intended to “capture the energy of urban Boston and its relationship with the shifting natural world it occupies.” Lanning went on to present the piece in Jordan Hall at a showcase of New Music by DMA Composers in February.

“Living in Boston today,” the program reads, “it’s hard to imagine that in about 70 years, give or take, a lot of the city will be underwater or routinely submerged. That is, however, the reality of our climate crisis. Boston won’t become Atlantis, but severe flooding will become the norm, and certain areas will be flooded or submerged at all times. If we fail to act, Boston and other cities across America and around the world will cease to exist as we know them.”

Students embraced more contemporary influences with performances of “4 Degrees” by ANOHNI and “Orange” by Pinegrove; the program notes for these pieces invited the audience to consider the wildfires that swept through enormous portions of Canada during the summer of 2023 along with the essential role forests play for ecosystems throughout the planet.

“It’s only four degrees, it’s only four degrees, it’s only four degrees,” sang Helen Bultman ’25 with increasing urgency, performing ANOHNI’s climate crisis anthem, which references a projected increase in the Earth’s temperature (in Celsius) over the next century, which would have devastating consequences for the planet’s ecology.

The physical concert program was a work of art in and of itself, designed by violinist Tara Hagle ’26. The eight pieces performed were represented with graphic drawings and text selections written by students and excerpted from meaningful pieces of literature. Each piece was paired with a QR code that took viewers to websites containing additional information, educational resources, and ways to take action.

Learning Outcomes

As students reflected on their experience in the classroom and in rehearsal for What Washes Over, the fulfillment of collaboration and the development of brand-new skills were common themes.

As a classical violinist, Hagle was unaccustomed to collaborating with musicians across genres and experimenting with alternative music-making methods when she entered this course. "My favorite part of putting this all together was the variety of skills I had to work on personally, as well as the amount of new approaches to creating music that I was able to experience," she said. "It was a huge challenge for me to let go of some of the processes I was used to, but I grew so much and met so many new collaborators throughout the project."

Rawlinson reflected on the vast array of roles and skills they took on during the course. "I got to be not only a violist but also an audience member, a stagehand, a tech assistant, a reader, an electronic artist, and a point of colloquial discussion and affirmation for other folks who were present—and that was so fulfilling for me," they said.

"A concert at a conservatory is a great place to break genre barriers," said Judson. "This class helped with my personal hesitations about creating work that engages with concrete, tangible, global issues. It gave me not only the motivation but also a set of tools to engage with these problems in a way that feels meaningful without being heavy-handed or unartistic."

For Gatlin, the course exceeded expectations in terms of the profundity of class discussions and the level of consideration and collaboration students displayed in planning and performing their concert.

"Perhaps what surprised me most was the care and energy students put into collaborating," she explained. "We had discussions and even debates on what qualified as climate action, the potential and limitations of portrayals of apocalypse or messages of hope, communicating information in engaging ways, getting away from conservatory elitism, creating a community space where everyone felt welcome and comfortable. I've always thought that one of the primary barriers to action is a lack of community and, thus, a lack of a sense of efficacy. Students created this community on a micro-level within the class, but also showed its expansive possibilities through discussions with others outside of class and through the many collaborators and audience members they gathered for their performance."

An Integration of Theory and Practice

NEC’s integrative curriculum blends classroom learning with real-world applications, an innovative initiative that significantly departs from traditional conservatory methods. New courses added to the curriculum are designed with the fundamental premise that when coursework is integrative, students come away with skills that go well beyond the singular context of music but are versatile enough to adapt to whatever career path they pursue.

“The conservatory education is based on a model that’s 200 years old and hasn’t changed terribly much in that time,” said Benjamin Sosland, NEC provost and dean. “But the world around us has changed significantly. We ask our students to do so many discrete individual things, but with these integrative courses, they are getting a whole meal.”

During Climate Change Culture and Performance Practicum, students got that “whole meal” and then some. They gained an understanding of climate science, cultural studies of climate change attitudes, the sociology and geography of climate injustice, climate change media, representations of climate change in art, and methods of engaging audiences across the arts — which was just one-half of their coursework. They also acquired invaluable professional skills through the project-based Performance Practicum, using their new knowledge to design, produce, market, and execute a live concert in collaboration with their peers.

“I’d emphasize that students were inspired and motivated by the fact that they could do work they would not do anywhere else in the curriculum — and they were able to lead in defining the shape that work would take,” reflected Gatlin. “Our students are ready to create art and define musical careers in new ways we haven’t imagined. Let’s provide them some of the support, academic and cultural knowledge, exploratory space, and practical tools to do so.”

Our students are ready to create art and define musical careers in new ways we haven’t imagined. Let’s provide them some of the support, academic and cultural knowledge, exploratory space, and practical tools to do so.