This spring at New England Conservatory, a group of violin students in faculty member Ayano Ninomiya’s studio embarked on a creative project never before attempted. They were challenged to arrange the Dichterliebe, A Poet’s Love song cycle, composed for voice by Robert Schumann based on the poetry of German romantic poet Heinrich Heinne, for the violin.

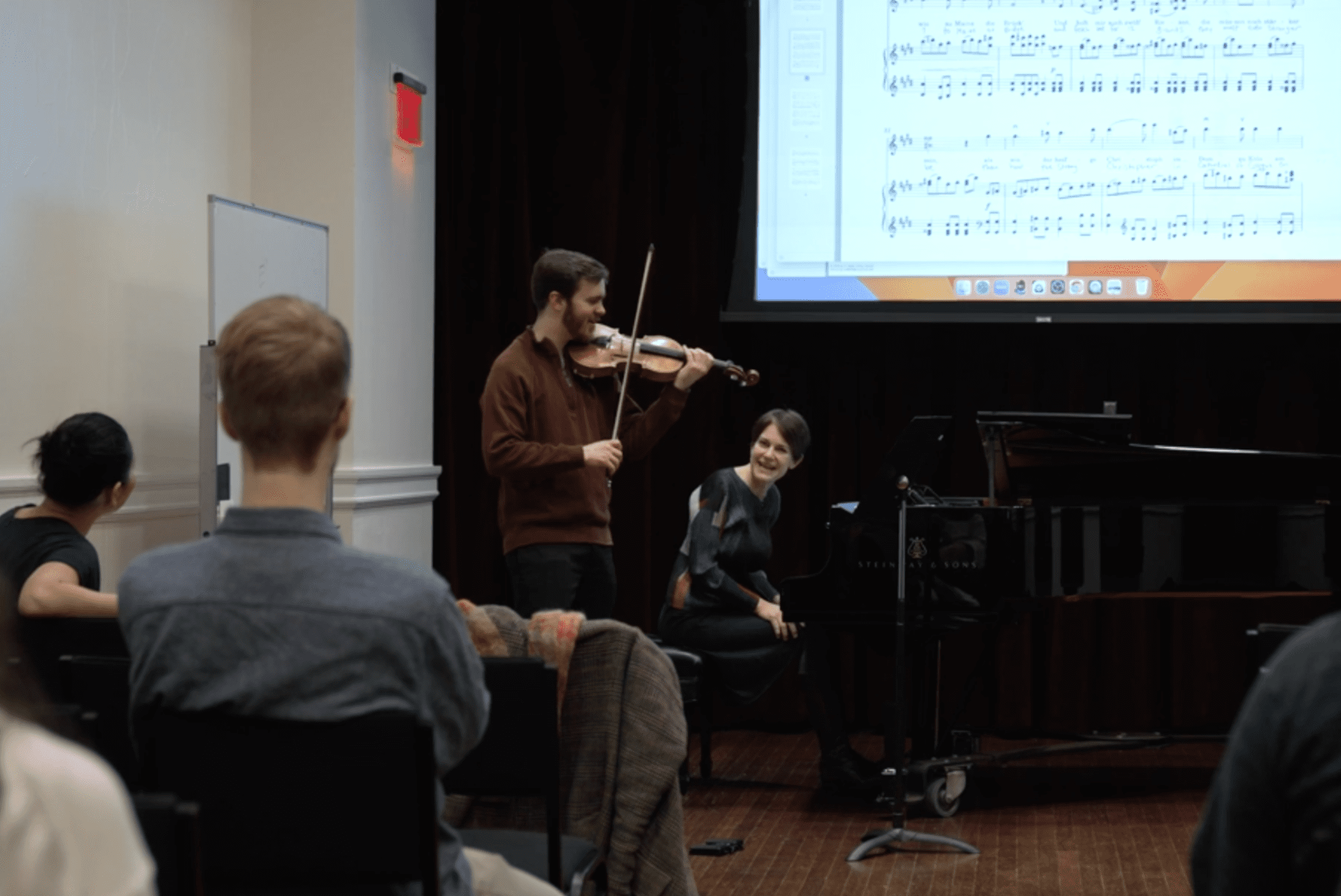

To do so, students would collaborate on a musical notation system to be used in the translated scores of each approximately one-minute-long song. Ninomiya partnered with vocal performance and collaborative piano faculty member Tanya Blaich to assist them, who provided expertise in German language, lieder, diction, vocal coaching traditions, and piano performance.

Ninomiya, an award-winning violinist who has taught at NEC since 2015, chooses a different topic for her studio class each year. She was inspired to explore the Dichterliebe during the spring semester because it allowed her to dive deeply into the art song genre with her studio students, a mixture of NEC undergraduate and graduate students.

“In history, the violin has imitated the voice,” said Ninomiya. “The voice has always been the ultimate expression vehicle, and so on the violin, we can learn so much about breath and phrasing and articulation.”

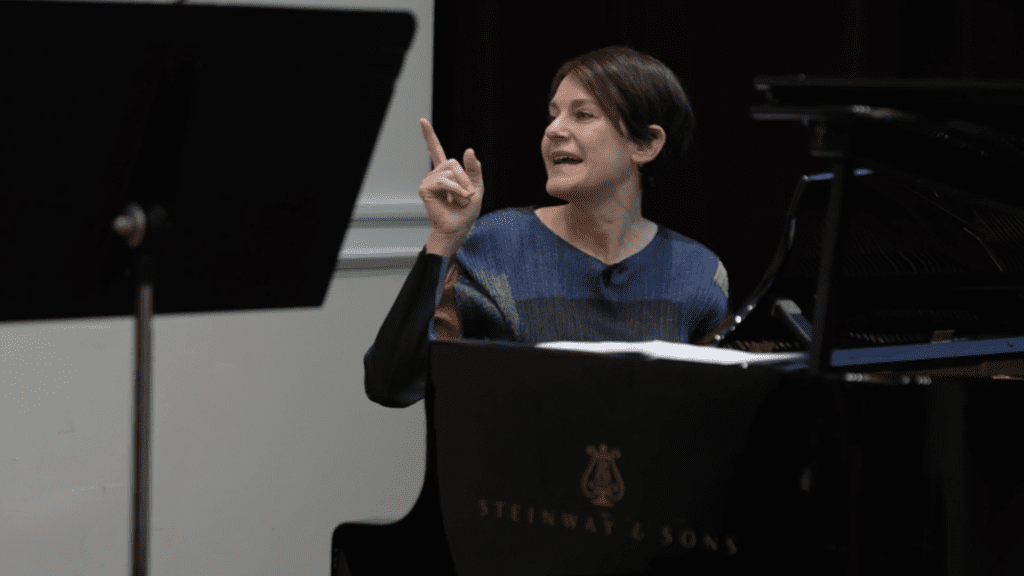

“Singing — the first musical instrument, and the one we all possess at some level — teaches musicians so much about lyricism, body resonance, and breathing musically,” said Blaich. “I sing when I practice piano, regardless of the repertoire, to understand phrasing and expression more intrinsically.”

The Dichterliebe song cycle was brought to life by Robert Schumann in 1840. During that year, Schumann was finally able to marry his longtime beloved, Clara Wieck, for whom he composed over 130 total Lieder. Overcome by emotion and creativity, he spent the year immersed in songwriting, setting to music dozens of poems by the great German poet Heinrich Heine. Among the most famous music to come out of this prolific year for Schumann was the Dichterliebe, A Poet’s Love song cycle.

Each student in Ninomiya’s studio was tasked with arranging between one and three songs from the Dichterliebe, editing their arrangements using specific details from their analysis of Heine’s original poems and Schumann’s musical treatments. Through exploration and practice, the goal was for the violin arrangements to mimic as much of the lyricism and emotional tone of the songs as possible through their instruments, despite the songs being written initially for voice, through which it is possible to convey so much with words.

The music of Robert Schumann, and the Dichterliebe in particular, had profoundly impacted Ninomiya at a young age. “It was very formative for me to hear this cycle in middle school and then to look at the text and realize what musical decisions Schuman made depending on the emotion or the context of the writing. It was incredibly inspirational to me,” she said.

For many of Ninomiya’s students, a translated arrangement like this was a creative challenge. “I have worked with vocal music before and learned to react to it in the past while playing for Bach cantata arias, but doing a transcription to this level of detail is new to me, especially trying to mimic the voice so closely,” said student Clayton Hancock ’24.

Before they dove into transcribing and arranging, Blaich introduced the class to the historical context of Heine and Schumann. She brought a deep expertise and personal love of these songs to the studio, helping students understand the complex emotions — love, rejection, despair— behind the words and music.

“I have lived with this cycle for over 30 years now, having first learned it during my studies in Vienna,” said Blaich. “I was first and foremost attracted to the music, and I don’t think I understood the deeper nuances of Heinrich Heine’s poetry until much later. I remember playing this for the final round of the Schumann song competition in Zwickau in 2000, where we won the first prize, and one of the jury members challenged me to dig deeper into the post-Romantic world of Heine. Now, more than 20 years later, I am reevaluating the meaning of the poetry and its relationship to Schumann’s extraordinary music and how it might translate into the unique voice of the violin.”

The studio class met 12 times during the spring semester, beginning with discovering Heine’s poetry and recordings of the Dichterliebe. Students engaged in discussions comparing different recordings of each song — including debates on what musical choices were made, how each expression related to the original text, and the role of the pianist in all of it. Ninomiya challenged students to consider the words they would use to describe the range of sound colors, expressions, articulation, and energy in each song. “Not just loud and soft!” reads the syllabus.

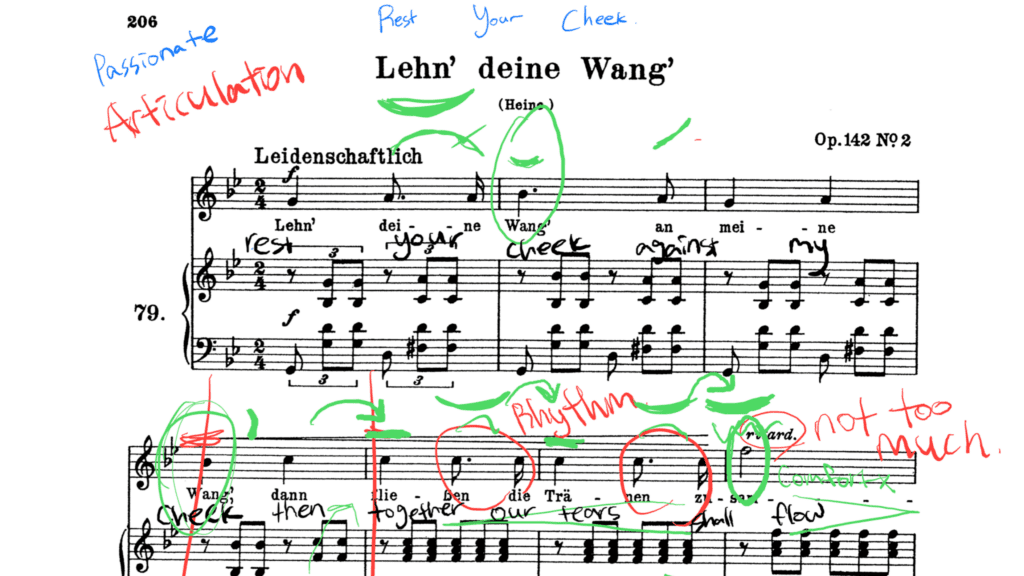

A significant part of the students’ challenge in translating the Dichterliebe for the violin was formulating a clear and concise notation system to use in their scores. The class worked together to develop a system that visually represented anything they would need to signify within their scores, including choices for vibrato coloration, timing and rubato, sound intensity, and depth color, methods of sliding from note to note, bowing portamento possibilities, and more.

“During one class, we examined how Beethoven notated his score. We also looked at some of Nick Kitchen’s research on manuscripts and discussed other composers’ designs, especially those who have been very specific about how to use the bow and how much,” said Ninomiya. “It was very creative, and everybody was full of ideas. Some students looked at how digital platforms display music notation, while others argued that handwritten notation is much more expressive. It was a lively discussion.”

“Unifying our notation system for matching diction has been an unexpectedly challenging endeavor, but it demonstrates artistic integrity and faithfulness to the original songs,” remarked Hancock.

Each student was assigned one to three songs to arrange for violin, allowing them to study each song in profound detail. This intentional element of the project, explained Ninomiya, gave students sufficient time to decipher and comprehend the layers of meaning and irony in Heine’s poems. Somehow, the translated violin scores needed to reflect the characteristics of the German language, moving beyond the meaning of individual words or phrases and illustrating syntax, cadence, inflections, articulations, breaths of the vocal traditions, and more.

“We tailored the project by asking students to be highly specific, to go deeply into the text, and then decide on what to do with every note,” said Ninomiya. “To take a one-minute work and really dive into it and make all those decisions was eye-opening for them.”

“Together with Ayano’s guidance, I saw students daring to explore a sound world that was out of their comfort zone—for example, some harsh, ugly, and frenetic sounds if the text warranted it, or fragmented and abrupt phrasal endings if the text syntax demanded it,” said Blaich.

Violinist and composer Tara Hagle ’26 reflected on the initial peculiarity of transcribing vocal lyrics for her instrument: “As an instrumentalist, I had never really thought about the added layer of text. It’s interesting how you are both bound to the text—as in you have to comply with the diction because the rhythm of music often reflects syllabic stress—and that, at the same time, it is such an expressive tool.”

The dynamic partnership of Ninomiya and Blaich created a unique, deeply reflective learning environment for students receiving active coaching from two of the finest musicians in their respective fields. For Hagle, Ninomiya fostered a musically curious, imaginative environment. “Ayano’s creativity and excitement are infectious, and I’m thankful to have the space in her studio to be creative and flexible and to be constantly exploring all the possibilities while, at the same time, also learning how to make informed musical decisions that communicate what I want to share with the audience,” she said.

Simultaneously, Blaich brought the historical context and language expertise that grounded the work. “Tanya’s knowledge of vocal conventions and tradition places these songs in context, which is so helpful in informing our approach,” she continued. “For example, she mentioned that Heine’s poems often have a sort of sarcastic sincerity that subverts German Romantic tropes, which completely changed how I interpreted certain moments in the music-to-text relationships. Having someone who can provide that context adds so much depth.”

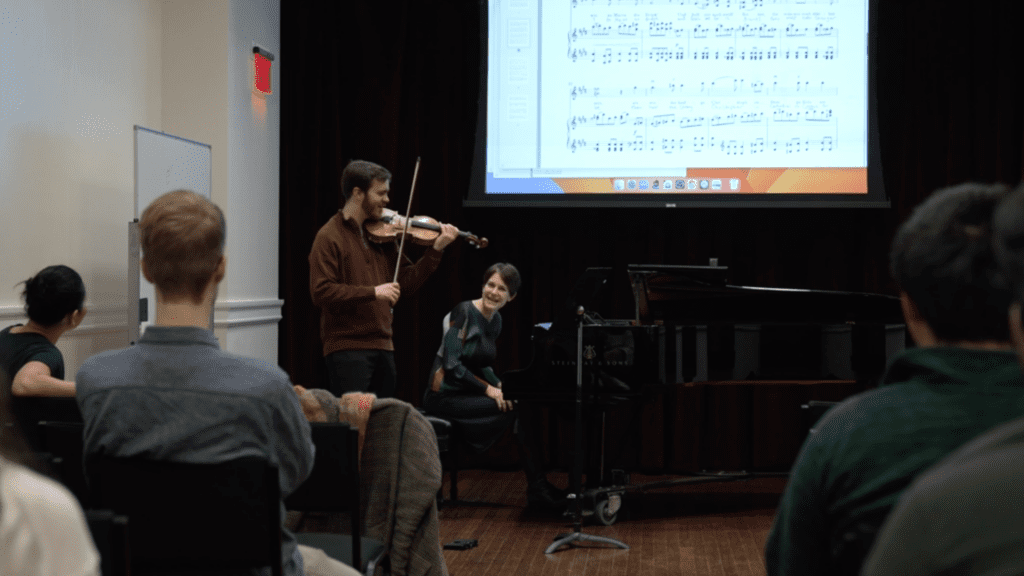

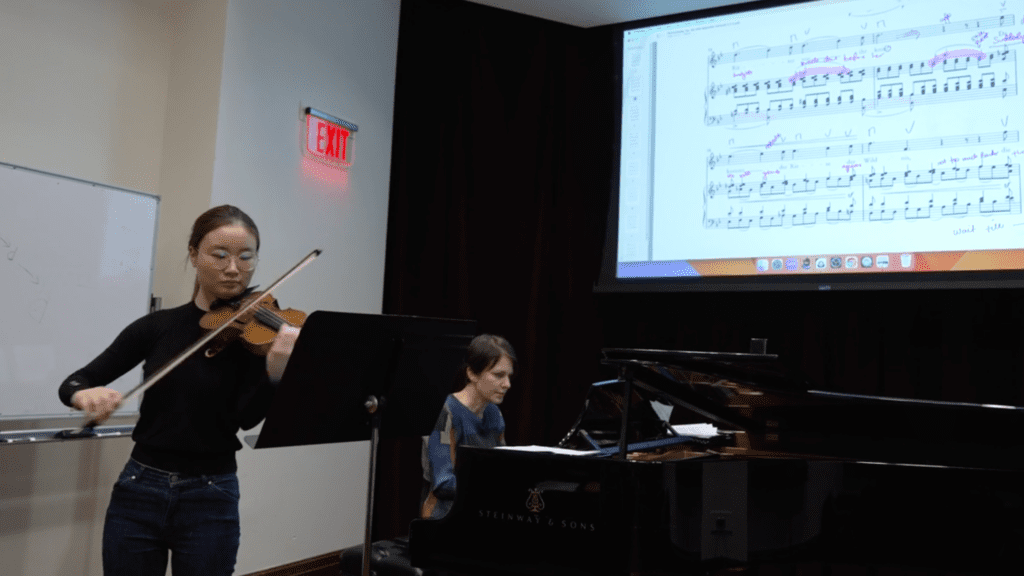

The class spent several sessions workshopping each student’s scores in partnership with four collaborative pianists — Solomon Ge ’25, Sandy Li ’22, Pualina Lim ’23 MM, ’25 GD, and Rafe Schaberg ’23, ’25 MM — and with thoughtful coaching from Ninomiya and Blaich. During one such session, Ninomiya urged her students to ensure they utilize the limited time available during their scores to connect with the audience and immerse them in the story through their sound. “If you could distill your song into just a few words or a sound or some kind of theme, then you’re going to bring us into this very vibrant world,” she said to the class. “It has to really grab us with the sound and articulation you’regiving every note. Don’t shy away—you have so little time to say something.”

After weeks of coaching and refinements, students were prepared and eager to share the Dichterliebe song cycle, reimagined for violin, with the world. On April 23, they performed original violin scores of all 16 songs (and four additional songs taken out before the cycle’s official publication) for a crowd of music lovers at Carriage House Violins down the street from NEC’s campus. Hancock addressed the audience during a brief speech ahead of the concert: “Welcome to Heine and Schumann’s world, where flowers and nightingales whisper to you about love, memories, and dreams haunt you, fairytales, and whimsical gardens captivate you, and cathedrals, giants, and knights roam in your imagination.”

Ninomiya, who remarked on the enthusiastic reaction of audience members to the performance, was delighted with the final result of her students’ work. She was pleased to hear and feel each violinist’s unique voice come through as they played their arrangements. “The song cycle stood on its own as a violin cycle,” she said. “Before we began, I had doubts that this could work for the violin without a text, but in the end, it was so beautiful. I was thrilled with how it turned out.”

“It was a lot of fun to see everyone’s interpretations one after another, and I also really felt a range of emotions listening,” said Hagle. “Just as Heine’s poems and Schumann’s music express such a wide variety of emotions, I think everyone brought a unique and personal touch to their songs based on all the work they did.”

This spring’s Dichterliebe studio class project was emblematic of NEC’s Integrative Curriculum, a comprehensive and inventive approach to the traditional conservatory model that combines the many elements of a conservatory education in new and dynamic ways to nurture each student’s artistic voice and professional development and equip them with a comprehensive range of core musical and management abilities. Beyond expanding their craft as violinists, the project enabled students to learn and integrate numerous skills at once — they dove into the art song genre and its place in history, gained an in-depth understanding of German romanticism, and honed a meaningful ability to discern the relationship between text and music.

For both Hancock and Hagle, the impact of words and diction on music-making is something they will take away from this studio experience into their practice as violinists. “Ultimately, instrumentalists should always have some sort of vocal element to their playing since that is the most natural form of sound we know how to make,” said Hancock. He also noted the benefits gained in creative project building, which he will integrate into his career as a professional musician. “From advertising and public speaking to performing and decorating, we covered all aspects of a real production together as a studio,” he said.

Hagle appreciated the high level of detail and intentionality that went into the project and strives to replicate this approach with any piece of music she composes or encounters going forward. “I always want to have a reason why I make a musical choice,” she said. “When we are constantly inundated with so much information, and when the pace of life is so fast, it’s really important to take a second and look around, thoughtfully observe, and find little moments of inspiration wherever possible. The more we note these special little things, the more tools we will have to experiment with in our music-making processes.”

Below, watch Ayano Ninomiya’s studio students perform the Dichterliebe song cycle reimagined for violin.