Tanya Blaich, voice and piano faculty member at NEC, discusses her research on female composers that inspired the programming for “Liederabend LVI: The Ungifted Sex: Pioneer Women Composers of Song in the 19th Century.”

This year’s musical programming at NEC features a particular focus on the history of female musicians and composers, who are often neglected in narratives and performances of classical music and other forms. This focus was highlighted by the Liederabend program on November 3, 2021, titled “The Ungifted Sex: Pioneer Women Composers of Song in the 19th Century.” The concert showcased the works of all female composers as part of an annual Collaborative Piano department series on historical “art song,” which includes poetry in French, German, and other languages, set to music.

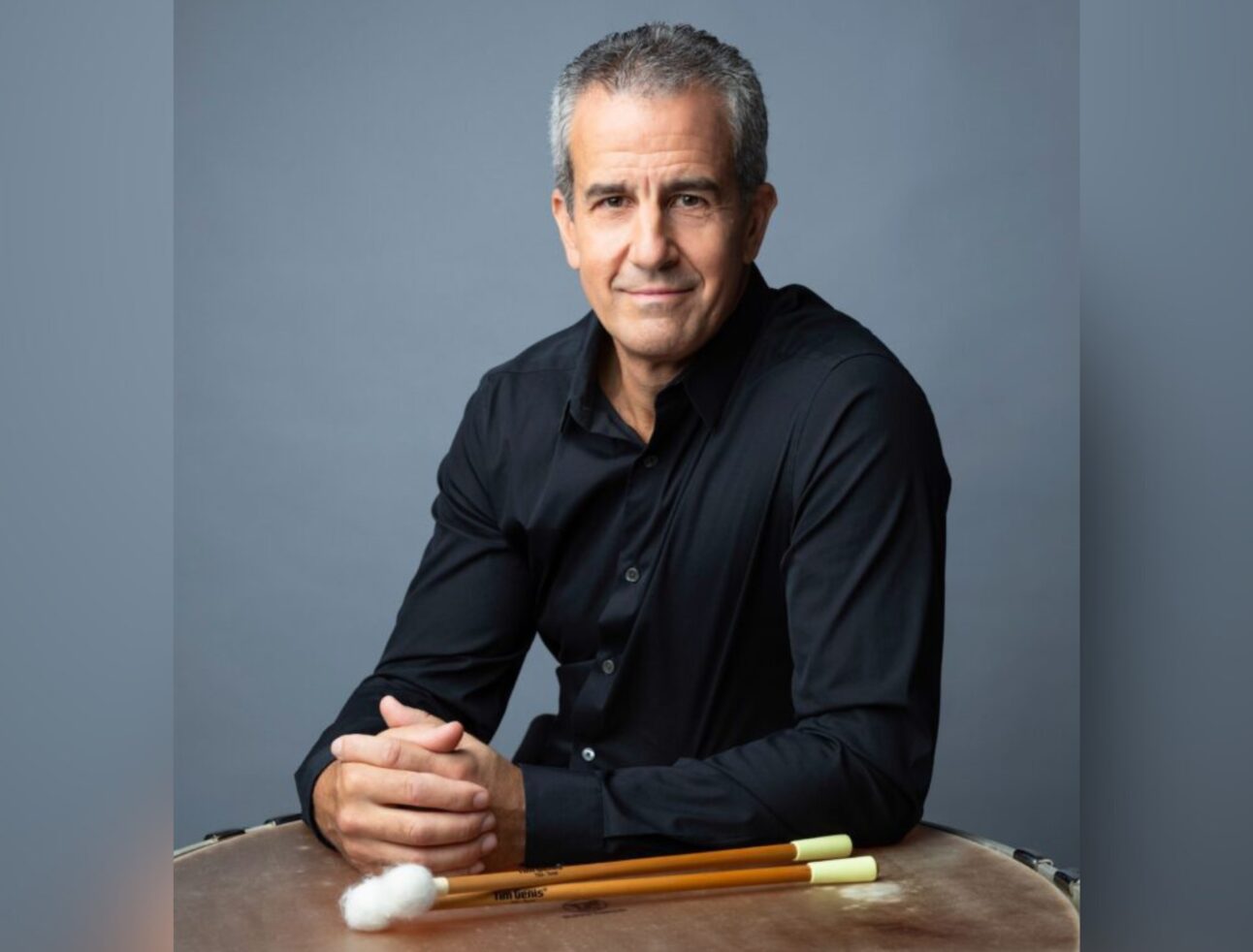

Tanya Blaich, voice and piano faculty member at NEC, is one of the directors and coaches of the Liederabend series, and we spoke to her to learn more about how these pieces were selected and what she discovered in the process. In our conversation, she discussed how she learned about 19th century female composers who defied the gender norms of the day to persist in writing incredible pieces of music—from Josephine Lang to NEC’s own Florence Price, a female composer who was doubly discriminated against as a Black woman. Blaich remarked that she was struck by the fact that she and her fellow professors and music experts had not known more about some of these female composers, which illustrates just how neglected study and performance of them has been in general. Now, that is finally beginning to change.

Read on to hear more about Blaich’s fascinating research for the program, the startling facts she learned about these composers, and the inspiring examples that should resonate not only for female musicians and composers of today, but for all who play, compose, and love music.

What originally inspired you to choose the theme of the concert?

It all started last summer when I read an article about Pauline Viardot’s 200th anniversary, and I was stunned by her life’s achievements and her rich musical career—a composer, opera singer, voice teacher, arranger, editor, collector of folk songs, director of an artist salon in Paris, spoke six languages fluently, was hugely influential on the careers of Saint-Saëns, Liszt, Gounod, Berlioz, and Fauré…sure, I knew some of her songs, but why did I not know more about her? And so I began to explore other women composers from this time period.

Another composer that I knew little about was Ethel Smyth, British suffragette and composer of many songs, orchestral works, quartets and operas; one of them was the first opera by a woman to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera (the second, by the way, was 113 years later, in 2016…) And the list went on.

Tanya Blaich:

How did you research and select the composers that were included in the program? What was that process like?

My readings on Viardot brought up names of other women composers that I knew next to nothing about—so I kept following these leads and read article after article. Another inspiration last year came from Graham Johnson, in a master class for our Song Lab class on Heine song settings, and he mentioned that Maude Valerie White’s settings of Heine were some of his favorites. Again, the stunned thought in my brain: “Who’s that?”

Along with my readings, I listened to as many recordings as I could get my hands on, and I not only discovered composers I had never heard of, I also discovered wonderful songs by Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn that I had never heard before.

My explorations went well beyond the scope of the program that was offered on November 3rd. But I wanted to focus the program in some way, so I decided to limit it to composers that were born in the 19th century—a time when song really began to flourish, and a time when women composers faced so many barriers.

A critic wrote in response to Germaine Tailleferre’s compositions: “A woman’s composing is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs—It is not done well, but you are surprised to find it done at all.”

Yet all of the women composers on this program, the supposedly “ungifted sex,” defied these widespread prejudices and stereotypes, and persisted in song composition! Awe-inspiring!

Were there any particular composers (and their backstories) in the program that stuck with you for any reason, or in which you found particular inspiration? If so, why?

I was completely bowled over by Ethel Smyth’s enormous compositional output, and her stamina in facing such retribution for her political activism as an advocate for women’s voting rights—she went to prison for it! I was inspired by her courage to live according to her convictions, both in her public and private life—she was a pioneer on so many fronts. She lived openly as a lesbian and dedicated the song I programmed in this Liederabend, Possession, to her lover, Emmeline Pankhurst, the founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union.

Another shocking backstory is that of Germaine Tailleferre’s Six chansons françaises: she wrote them after her first husband threatened to shoot her in the stomach upon hearing she was pregnant with their first child—she heard shots in the house, ran away, miscarried because of the trauma, and then divorced him; two months later, she had completed these songs. Some of the 16th century texts she set here address abusive husbands with a sense of irony and even humor, and some scholars say that composing these songs was, in a way, her therapy in working through the trauma.

The other backstory that really moved me was Florence Price’s—maybe because she studied here at NEC, or because she faced double discrimination as a Black woman. For the Liederabend program, we had students read a quote from each composer before each set of songs, and the one I chose for her was an excerpt from a letter to BSO conductor Serge Koussevitzky, and it really gets me every time:

“To begin with I have two handicaps––those of sex and race. I am a woman, and I have Negro blood in my veins. Knowing the worst, then, would you be good enough to hold in check the possible inclination to regard a woman’s composition as long on emotionalism but short on virility and thought content, until you shall have examined some of my work?”

Was there anything you learned as you put the program together that surprised you?

I was surprised by the tenacity of these women! Everything was working against them—the pervasive gender norms confined women to the domestic realm as wives and housewives. I was surprised that so many of these women were able to transcend these norms; consciously or unconsciously, they managed to jump ahead of their time and reimagine their worlds despite societal norms. Even though we’ve come a long way in terms of gender equality, I was also surprised to realize how some of the prejudices I read about then are still alive and well today.

“I feel I must fight for my music because I want women to turn their minds to big and difficult jobs, not just to go on hugging the shore, afraid to put out to sea.“

Ethel Smyth